Physiognomy 400–A Special Study: The Military Role

On July 4th, 1802, the West Point Academy was officially opened.

Physiognotracing has its limitations and its benefits. Its limitations are mostly in the way in which it is produced. When we have a silhouette we have only two of the three dimensions that make up the face. When we have a detailed portrait we have a clear vision of just one side of the face, the view of someone and someone’s personality from just one perspective. This has its good and its bad features. Its good features are that we can pretty much define the character is someone using the traditional physiognomy line of thinking for the time. We know whether or not a person has the nose and mouth of a donkey or rame, or whether or not he/she is intelligent and designed for some sort of financial enterprise. But we never really know everything about the individual unfortunately due to the image of just one side of the face, no matter how well it was produced be it in black and white or in color.

Nevertheless, this knowledge about a person served a purpose, especially to the government and to the military. If you were someone the military was searching for, like a horse thief turned enemy or an attractive young lady turned spy, you might be able to be distinguished from others in a crowd consisting of your look-alikes by a well-trained “Lavaterist” or specialist in facial patterns recognition. As a policeman, member of the militia, government spy, or even patriot for a cause not yet revealed, you probably would like to know everything possible about someone you are secretly watching, especially your enemies. This is where Lavater’s pocket guide to face reading or physiognomy came into play in and around internationally frequented communities along the Hudson River, especially near West Point.

Previous Owner – “Army Medical Library”

In 1817, just after the second battle with the British had ended, and

just a few years after the Napoleanic War, and a few years longer after

the French Revolution and various disputes taking place between

European nations, such a book was published and became the material of

the army library. This book, The Pocket Lavater, was a pocket

guide that could be carried about the fields of activity, war and

surveillance, enabling a soldier to learn everything possible about the

enemy and in particular the most influential leaders serving the cause

for the enemy. Instead of a book on how to interpret Spanish

signs, French newspaper articles, or ask a Persian wher ethe closest

hotel was, this book enabled you to gaze at a person’s eyes, from a

distance, and by focusing on his/her features, develop an idea on what

to expect when you decide to walk right up to him or her and ask her for

some important information. The Pocket Lavater told who you

could trust and distrust, and who you could even try to engage in some

pre-planned conversation with knowing that he/she was not to be trusted,

and most likely would reveal the most intimate parts of whatever you

told her with her local acquaintaince or governing official, your enemy..

From Jules Verne (1828-1905), The Moon Voyage, Chapter XVII. (http://infomotions.com/etexts/gutenberg/dirs/1/2/9/0/12901/12901.txt).

He was a man forty-two years of age, tall, but already rather stooping,

like caryatides which support balconies on their shoulders. His large

head shook every now and then a shock of red hair like a lion’s mane; a

short face, wide forehead, a moustache bristling like a cat’s whiskers,

and little bunches of yellow hair on the middle of his cheeks, round and

rather wild-looking, short-sighted eyes completed this eminently feline

physiognomy. But the nose was boldly cut, the mouth particularly humane,

the forehead high, intelligent, and ploughed like a field that was never

allowed to remain fallow. Lastly, a muscular body well poised on long

limbs, muscular arms, powerful and well-set levers, and a decided gait

made a solidly built fellow of this European, “rather wrought than

cast,” to borrow one of his expressions from metallurgic art.

like caryatides which support balconies on their shoulders. His large

head shook every now and then a shock of red hair like a lion’s mane; a

short face, wide forehead, a moustache bristling like a cat’s whiskers,

and little bunches of yellow hair on the middle of his cheeks, round and

rather wild-looking, short-sighted eyes completed this eminently feline

physiognomy. But the nose was boldly cut, the mouth particularly humane,

the forehead high, intelligent, and ploughed like a field that was never

allowed to remain fallow. Lastly, a muscular body well poised on long

limbs, muscular arms, powerful and well-set levers, and a decided gait

made a solidly built fellow of this European, “rather wrought than

cast,” to borrow one of his expressions from metallurgic art.

The disciples of Lavater or Gratiolet would have easily deciphered in

the cranium and physiognomy of this personage indisputable signs of

combativity–that is to say, of courage in danger and tendency to

overcome obstacles, those of benevolence, and a belief in the

marvellous, an instinct that makes many natures dwell much on superhuman

things; but, on the other hand, the bumps of acquisivity, the need of

possessing and acquiring, were absolutely wanting.

.the cranium and physiognomy of this personage indisputable signs of

combativity–that is to say, of courage in danger and tendency to

overcome obstacles, those of benevolence, and a belief in the

marvellous, an instinct that makes many natures dwell much on superhuman

things; but, on the other hand, the bumps of acquisivity, the need of

possessing and acquiring, were absolutely wanting.

There is no direct evidence suggesting that West Point actually made use of Lavater’s philosophy to learn about the enemy. But the important need for such skills were forever present. In 1812 the second war with Great Britain began, yet the relationships between the United States, Great Britain and France were almost constantly unstable, and at times close to turmoil. There was ongoing trade related issues, particularly dealing with the release of British goods to other countries. Like most countries during these first years of the 19th century, the local population was experiencing growth spurts, thereby tasking the local sources for foods, clothing and other necessities within the urban environment. There were no well established methods of dealing with the poor, only almshouses and new bills often passed in their most infant of forms. The government was constantly trying to place the pressure of dealing with the poor back on local communities. Malthusianism was at its peak in popularity since the first publication of this essay in 1798, which by the time of its second publication in 1804 seemed to be explain the insurmountable social problem that most developing countries were now facing.

A Military Officer’s Evaluation of Character using Lavater’s Book (Lavater’s entire book will be posted in the future.)

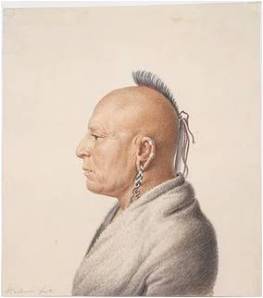

This first example of a physiognomy character with potential miltary interpretations in found in Chapter 26 of Lavater’s book, which is interpreted as the face of a villain.

This person does not look at all like anyone you would want to trust, if he looks as though he were having a bad day.

. . . and oh yeah, Hannibal Lecter

Then there’s the ingenius and malicious spy. The traitor, if you

will recall, is someone who is going to do everything possible to reach

his or her goal of a national character and nature, but with the

personal touch needed to get things done in the appropriate manner. At

first, he comes onto you as a nobody. His lines don’t make sense at

all. He seems to talk as if he were in a world of his own, imagining

something that only he can see. So, you write him off as some waste of a

healthy body, where the head does little to match the form or

physique. Based on his west coast slanted forehead, typical of the

Indians you have often read about in recent years (a number of cultures,

for example the Flathead Indians of Oregon, 1840, engaged in this

process as a cultural tradition.). ’He has no brain’ you think, and

so you causally walk away.

Unknowingly, this stranger has just stolen the official papers from your pocket detailing the office that you work for. During his period of proximity to your body, he has also learned everything he needed to know about you such as the kind of pipe you smoke and brand of tobacco smoke that saturates your clothes. He also noted the offending odor of your breath and armpits, enough make anyone rush their encounter with you just to make you leave. There was also a sign of what you ate last night, indications as to why two of your side teeth have fallen out, how much alcohol you drink per day, and a slight gurgling noise or warning that should any borborygmus be heard, it was time to finish the task at hand and immediately see to it that you make your way out the door. He knows your favorite colors, the make of your wig, the tendency for your knees to pop and crack at times as you reposition yourself whilst standing.

Two infamous Revolutionary War spies - who most resembles ‘No. X’? who would you more likely trust?

With all that information stored in his little forehead, slanted

backwardly as if certain parts of his brain were removed, he has

unknowingly been able to now taken on your identity. It is not until

the next day that you learn about this mishap, and feel betrayed, not by

your incontinance, but instead by the point in his forehead that you

happened to miss. According to the cashier for your company, you, or

someone who said he was you, just walked away from your office, with all

your monthly salary in hand, smiling and making obnoxious noises as he

walked out the front door right by you.

Then there’s the miser. That individual you always heard about whom you felt unfortunate to not to have to get to know – – until now. The miser knows all the details about the occupants of his homes, which he rents for a little more than normal monthly price, but manages to keep in repair for incredibly less investments. His character is like that which went right into that Charles Dickens tale, just a decade or two after this personality was revealed for the first time and his physiognomy better understood by Lavater and other popular physiognomists. For the military man, the miser was good for the army. So long as they had the coinage he requested, they could gather from him unlimited amounts of privileged information on anyone he has had interactions with. What better way to learn about a local renter receiving regular mail from the British Army, or the local man considered “blind and dumb”, receiving regular compensation for services performed in France or Italy. There was no better way for the army to distinguish their truth-telling informal spies from their liars, but Lavater’s book made all of this possible, for just a few half-pennies out of your pocket.

Historically famous misers

The most productive use of this book by the military perhaps

pertained to the studies of past Generals and other highly successful

leaders. To know your enemy, you had to think the way that he did. In

the case of the military, it was the character, demeanor and personality

of the highest ranking leaders that had to be known by the Lieutenants,

Colonels and Generals to be. According to this philosophy, a member of

the militia could glance at someone like Napolean and in theory have

him categorized down to his most important personal and professional

features. If we were to take this role of the first impression

seriously, we might consider Napolean to be somewhat phlegmatic, and

overly melodramatic. This was reflected not only in his dress, but how

he manicured himself and tended to his hair as told by the paintings and

physiognotraces, as well as also by his tendency to ride on horseback

above the military, as if he had a short person’s complex, and how he

had his soldiers fight. With the military taken to its limits at times,

it took only the surprise nature of small rockets to make his militia

seem far stockier and harder to fight than perhaps they actually were at

times.

If we take a close look at Napolean using the Pocket Lavater as our guide, we find a complex man who is either “tranquil” and “timid” and not yet achieving (24), or someone who is or an “extraordinary genious” (20). As a General of the French or English Armed Forces, which of these two might you pick?

It is not so much the nose as it is the forehead that gives away Napolean’s true character, as much as his forehead. This probably suggested to some of Lavater’s most devoted followers that the forehead of a military is the best way to judge him as a military man (this is of course very much speculative). ‘But just how smart is he?’, you may ask as an officer. The other features, his eyes, nose and chin tell you enough about his persona, his personal traits and skills, or lack thereof as a leader, that you can now answer this important military question. Why go to battle, against people you do no know? Had he the forehead of a Flathead Indian, you might ask, (as per recent accounts due to Lewis and Clarke,) you need not worry so much about his cognitive and cunning planning skills, although his ability to perform as a soldier might not be any less.

Why mention this possible use of physionotracing at West Point? It ends up, this probably came about due to the help of one of its professors.

This professor began his teaching as a teacher of the French Language, his occupation a by-product in Amereican due to the French Revolution at his former home base. But his accomplishments as a french teacher would soon be made minimal in comparison with his contributions to the local physiognomy professions. In 1822, he wrote his own version on the writings of Gall about facial form and meaning, thereby promoting it locally and subsequently making it a requirements perhaps for certain types of students at this college.

As Sun Tzu and later George Patton once stated (roughly worded) “Know thy enemy, know thy Self.” During the years that this philosophy in the military sciences probably developed, James Tilton (1745-1822) was the Surgeon General of the Army from 1813 to 1815. During his later years of life, his face may have gone unrecognized by many of the students, but his character would have been well understood, in particular by those read in their textbooks. A past military officer and physician, his firm affect would have very much influenced the degree of success this school and the local militia would have for the next several years.

James Tilton (wikipedia)

.

Lavater wasn’t the only way to go with trying to interpret physiognomy if you were a military man. Everything out there that was published and availabe had to be taken into account. The ancient works of Greek and Roman scholars were also a part of the pocket guide to this science that the military was learning from. Porta’s physiognomy in which a person was matched with an animal according to facial features was a very common way to review this particular use of this interpreter’s skill. Aristotle and others determine animals to be symbols of who and what we are.

In the above silhouette of a famous character, we can see these parallels to such an extent that either they were a part of some original writer’s philosophy during the early 1800s, in particular from 1820 to 1823, when Last of the Mohicans was written. Just what did the character, and in this case actor reveal to us about the Native American-metis tradition? Aristotle, indirectly Porta, and the writer of Last of the Mohicans Cooper demonstrate proof for this association being made during this important period of American history. Perhaps even the casting director for the movie subconsciously had this association in mind.

The

stern face, well defined nose, prominent brow ridge, even James

Fenimore Cooper saw the avian character in the individual best known as

Hawkeye.

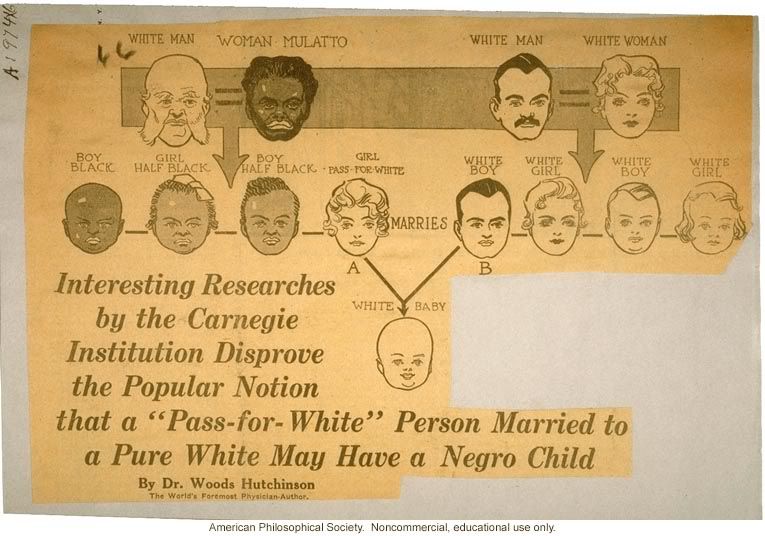

By 1825, the craft of physiognotracing had reached its peak, and was

beginning to dwindle. Like any popular culture fad, it had its

strengths and weaknesses throughout its period of permutation and

propagation. So many individuals were reinventing the wheel so to

speak, inventing tracing instruments that performed in new and unique

ways. What replaced physiognotracing was the development of a similar

skill that focused on the bilateralism and asymmetry of the face, head

and even brain. The face of a malformed individual could be drawn from

either perspective based on the original way of producing the

silhouette. The new methods becoming popular looks at the smallest of

features on each side of the face and overall cranium. In this way the

manic and possessed body and mind of a person with a misplaced soul

could be researched and explained in new ways. The melancholy of the

past was now the hysteria and mania of the present. Physiognotracing

set the stage for the development of the Gallists’ physiognomy into the

more detailed Fowlerist Phrenology. Phrenology in turn set the stage

for the evolution of physical anthropology as a scientific skill, not

just another form of fortune telling or personality interpretation. As

the lessons we received due to physiognotracing resulted in these

changes in the sciences, our knowledge of this unique and original skill

went away and even left the local history world. The mathematics of

this craft is what we now benefit from–the ability of a graphical artist

and mathematician to develop a computer program that will compare two

silhouettes or two three-dimensional facial traces in order to identify

just who you are, by camera, and this time without you even knowing

(airport facial recognition software). We can then determine who you

are by matching that face with your electronic history, a far cry from

depending upon just instincts, conversation, and extroverted behaviors.

More Web Visits and Readings

See http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/samples/cam031/00063010.pdf

http://www.uniphiz.com/digital_physiognomy/recognition-of-psychological-characteristics-from-face.pdf

http://www.archive.org/stream/physiognomyillus00simmiala/physiognomyillus00simmiala_djvu.txt

http://webscript.princeton.edu/~tlab/wp-content/publications/Todorov_YCN2008.pdf

http://www.robertthomasmullen.com/blog.html

14. Johann Caspar Lavater

The Pocket Lavater: The Science of Physiognomy

To which is added an inquiry into the analogy

between brute and human physiognomy, from the Italian of Porta

Van Winkle & Wiley, New York, 1817

The Pocket Lavater, one of Wiley’s earliest science titles and translations,

was derived from Physiognomische fragmente, by the Swiss scientist

Johann Lavater (1741-1801), with added extracts from Giambattista

Della Porta’s De humana physiognomonia. Lavater believed moral

character could be read in facial features, and Wiley’s handy pocket

edition used illustrations to teach the reader how to identify “the

physiognomy of . . . a man of business” versus that of “a rogue.”

Physiognomy was very popular at the time; at least 20 editions of

Lavater’s Essays were published in English before 1810, including two

in America, and by 1825, American periodicals had featured no fewer

than 70 articles on the topic. 12

The Pocket Lavater: The Science of Physiognomy

To which is added an inquiry into the analogy

between brute and human physiognomy, from the Italian of Porta

Van Winkle & Wiley, New York, 1817

The Pocket Lavater, one of Wiley’s earliest science titles and translations,

was derived from Physiognomische fragmente, by the Swiss scientist

Johann Lavater (1741-1801), with added extracts from Giambattista

Della Porta’s De humana physiognomonia. Lavater believed moral

character could be read in facial features, and Wiley’s handy pocket

edition used illustrations to teach the reader how to identify “the

physiognomy of . . . a man of business” versus that of “a rogue.”

Physiognomy was very popular at the time; at least 20 editions of

Lavater’s Essays were published in English before 1810, including two

in America, and by 1825, American periodicals had featured no fewer

than 70 articles on the topic. 12

![[Most Recent Quotes from www.kitco.com]](http://www.kitconet.com/images/quotes_special.gif)

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar